I was fortunate in my music-making days to get to actually play Beethoven on three different occasions.

The first came via my piano teacher in high school, a lovely old woman named Margaret Hooker. She lived alone in a nice-sized house in Olean, NY, with a quite lovely backyard and a large music studio with two pianos in it, and she was well known as one of the area's finest piano teachers. She had a lot of students, and her end-of-year recitals were always pretty big events. Thinking back on those recitals, I remember a lot of music, including one bad moment when I crashed and burned in the middle of the first movement of a Mozart sonata. There was one transition in that movement that always gave me fits, and I tended to nail it in practice no more than twenty-five percent of the time; the recital was not one of the twenty-five. I slammed to a halt, and Mrs. Hooker gently said, "Start right after that." And after that I was fine. A terrible, humbling moment--but I redeemed myself the next year, by gum! The next year I played the absolute hell out of something. A piece by Edward MacDowell, if I recall correctly. I tend to get really motivated when I screw up badly.

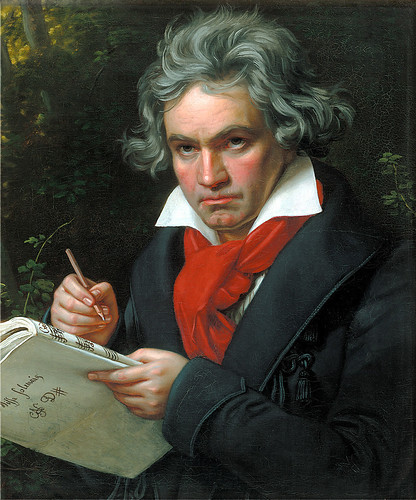

But anyway, Beethoven! Any piano student of any skill will play a Beethoven sonata, or a movement of one, sooner or later. For many it's the Pathetique Sonata, but for me it was other really common one: the Piano Sonata No. 14 in C-sharp minor, often called the Moonlight Sonata. This sonata, unlike many of its brethren, starts not with an allegro movement but with an adagio, putting the "slow" movement first in line. Still the form of the movement is that of a sonata-allegro movement, just in a very slow tempo that contrasts a series of arpeggios, repeating and repeating in hypnotic effect in the bass, with a repeated motif played by the right hand that struggles to be called a "melody". I loved playing this piece because it appealed to my inner Romantic: I could linger on this piece and take long liberties with the rhythms; so much so, in fact, that Mrs. Hooker actually had to intercede a few times to tell me that "it's slow, it's not a dirge."

I only played the first movement; though I did work on the second movement (a graceful minuet that I do wish I'd worked harder on), the year's lessons ended before I could really get it polished, and the next year we worked on other things. I never even tried the last movement, which when you listen to the entire work seems to come out of nowhere with its stormy fire. I remember asking Mrs. Hooker about it, and she bluntly said, "I never teach the last movement." When I asked why, she equally bluntly said, "I can't play it." She tried a few bars, and shrugged. "I can play a lot of things, but I've never conquered this one." You gotta respect that!

(On a food note, Mrs. Hooker's recitals are where I first learned about punch made by dumping an entire container of rainbow sherbet into a big bowl of 7-Up. I don't know why I thought of that just now, but there it is.)

Here's the Moonlight Sonata (named thus after Beethoven's death!), performed by Anastasia Huppmann.

I still studied piano in college, for three years, though I don't recall playing any Beethoven there. Beethoven did come up twice on the programs with the Wartburg Community Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Dr. Janice Wade (a professor to whom I took a strong initial dislike but came around rather quickly on; she ended up being one of my favorite teachers of all time, which is probably when I learned the lesson that I've carried with me for years, that first impressions are almost always bullshit). I don't recall when exactly the Symphony No. 1 in C Major was on the program, but I think it was in my sophomore or junior year. This symphony is certainly Beethoven, but it is also firmly closer to Mozart and Haydn than to the heights to which Beethoven would take the symphony later in his life. As a member of the trumpet section, I found the First Symphony kind of dull from a performance standpoint; when Beethoven wrote this, the symphonic trumpets were still valveless instruments, only capable of sounding specific harmonics, so there was a whole lot of sitting and doing nothing until the big tutti moments when the trumpets would play a tonic and dominant or two, before returning to counting rests. We were probably tacit for the inner movements. Still, the piece was incredible to hear as it came together, and that in itself was a valuable experience.

Then, in my senior year, Dr. Wade brought in three soloists to play the Concerto for Violin, Cello, Piano, and Orchestra, a work most often referred to as the Triple Concerto. This work is...well, it's a strange kind of work. The three soloists make for some odd writing, as I recall, and the trumpets had even less to do in this piece than in the First Symphony. So...and I admit this with no pride here...in the rehearsals I never played a note. I literally sight-read the damned thing at the dress rehearsal and again at the concert, and we were fine. That's what the Triple Concerto is: it's fine. It's actually kind of a problematic work, maybe for Beethoven the equivalent of Shakespeare's "Problem Plays". I'll let The Guardian explain:

Beethoven Triple Concerto: arguably the least successful of any of Beethoven's mature concertos in the concert hall. It's one of those pieces that never seems to get a performance that does it justice. Usually, you get po-faced seriousness when a big orchestra and three star names try to out-do each other, as the cello, violin, and piano soloists fight for the limelight. On disc, it hasn't fared much better, and there's an infamous Herbert von Karajan recording from 1969 with David Oistrakh on violin, Sviatoslav Richter on piano, and cellist Mstislav Rostropovich: it's a nadir of gigantic egos trying to trump each other, a bonfire of the vanities from which Karajan and the Berlin Phil still somehow manage to emerge victorious.

(Richter himself said of it: "It's a dreadful recording and I disown it utterly… Battle lines were drawn up with Karajan and Rostropovich on the one side and Oistrakh and me on the other… Suddenly Karajan decided that everything was fine and that the recording was finished. I demanded an extra take. 'No, no,' he replied, 'we haven't got time, we've still got to do the photographs.' To him, this was more important than the recording. And what a nauseating photograph it is, with him posing artfully and the rest of us grinning like idiots.")

...

The truth is that the Triple Concerto isn't a concerto at all, since there's no real dialogue between the orchestra and the soloists, and the three soloists carry virtually all of the musical argument themselves.

It's a nice listen. It's not bad, but if you're working your way through Beethoven, from the greatest works on down, it'll be a while before you get to the Triple Concerto and its not-terribly-profound geniality.

Here are the Symphony No. 1 and the Triple Concerto.

No comments:

Post a Comment