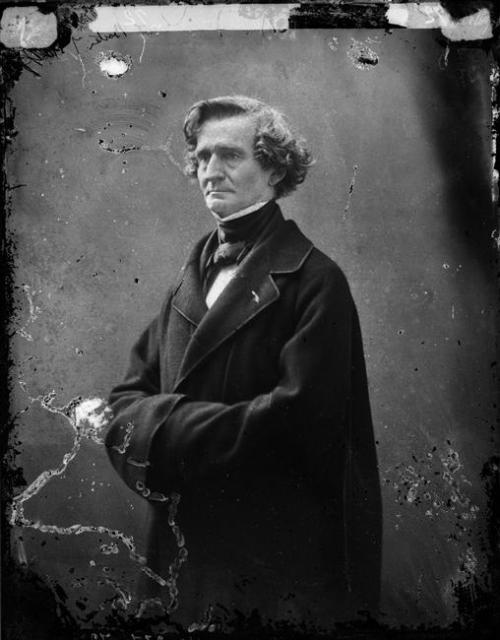

This is a repost of a piece I wrote -- oh my God! -- over ten years ago, on the bicentennary of the birth of Hector Berlioz. I'm reposting it as prelude to today's Symphony Saturday post.

In the movie Mr. Holland's Opus, there is a wonderful scene – one of many – when Mr. Holland's wife, Iris, is quite upset at her husband's under-enthusiastic response to her news that she is pregnant with their first child. Mr. Holland, of course, realizes how he's stepped in it, and he attempts to describe to his tearful wife his feelings about becoming a father. Like everything else in his life, he relates it back to music. What he says is this, in a rough paraphrase:

"When I was a kid I used to go to the record store every day, and the guy there would tell me what to listen to. One day he hands me a John Coltrane album and tells me to go home and listen to it. So I did, and I hated it. I mean, I just hated it. And I hated it so much that I had to listen to it, every day, over and over again, until I figured out why it was that I hated it so much. And while I tried to figure out why I hated it, I finally realized that I loved it. And to this day, I love John Coltrane. (beat) You telling me about our baby was like me coming to love John Coltrane all over again."

That pretty much sums up my experience with the music of Hector Berlioz.

It was a pretty prosaic introduction, actually: high school band, when I was in ninth grade. We had just performed our fall concert the night before, and now it was time to start on some new pieces for our winter and spring activities. Two pieces of sheet music I'd never seen before turned up that day at rehearsal: something called Le Carnival Romain by a guy named Berlioz, and something called March to the Scaffold, also by this Berlioz fellow. We attempted sight-reading Carnival for most of the rehearsal, but since we were a high school band we had to take it incredibly slow at first, and as anyone who's heard the piece will attest, most of it is a spirited vivace. Not the best way to make my acquaintance with Berlioz.

But then, the next day – that was when we started digging into March to the Scaffold.

So it's a March, I can tell. That means a pretty brisk tempo, right? That's what I expected, Mr. Young Band Student, after a steady diet of Sousa and K.L. King and "Entry of the Gladiators" and whatnot. But not this piece. It starts out with muffled drum sextuplets, which are answered by this weird syncopated figure in the low woodwinds. (No high school bandmember likes the sound of low woodwinds. Take it from a member of the trumpet section who used to join his brassplaying mates in inventing euphemisms for the low woodwinds that frequently involved metaphoric flatulent bovines. Luckily, I would later realize that those instruments do wonderful things. Like, say, the opening bars of March to the Scaffold.)

The piece went on, getting louder in places and having strange and sudden bursts of loudness from the brass – always fun – and then, at long last, a wonderful marching melody for the trumpets and the rest of the brass. (We trumpet players pretty much define the membership of any ensemble as "the trumpets and the rest of the instruments".) Now I was a bit happier; after some weird and jocular opening stuff we get to the "meat" of the March, and everything would be fine.

Except after that melody ends (it's stated twice, unless you observe the repeat which we did not), well, the March gets even weirder. The glorious brass melody is replaced with snarling, biting brass figures, the woodwinds scream, the rhythms become more insistent and driving, the guy behind me on the timpani starts pounding away, everything builds and builds and builds, and it gets crazier – until everything stops, and there's this tiny wisp of melody on a solo clarinet. This is cut savagely short two bars later by a resounding whack by the whole group, some descending woodwind notes, and then a series of fortissimo chords ending the whole thing.

It was all very weird, and I didn't understand any of it. The piece made no sense.

Well, we rehearsed that damned thing for a few days before the band director decided to reject it in favor of something else. At some point he let us in on the fact that the March to the Scaffold actually is a piece of program music. The story is simple: a guy is being "marched" to the scaffold where the guillotine awaits. He's going to his execution; hence the dark beginnings and the frenetic stuff in the second half. And that bit of clarinet melody at the end? That's the guy thinking of his lover one last time before the blade drops. Whack!

So, I thought, "OK, it's interesting. Big whoop. At least I'll never have to play that weird stuff again."

A few months pass, and I'm in a record store thumbing through the budget-priced cassettes. Something strikes me: a cassette with this Berlioz fellow's name on it. Picking it up, I see that it's a recording of something called Symphonie fantastique; and perusing the back of the thing, I see that the fourth movement of this symphony is none other than the March to the Scaffold. Intrigued, and made adventurous by the $3.99 price tag (I'm a lot more likely to be musically adventurous when the recording is cheap), I bought the thing and took it home. I played the tape a few times, mainly just skipping right to that March just so I could hear the way the orchestra's supposed to sound, and not a band arrangement (although it must be said that a lot of fine work gets done in band transcriptions). I had to admit, the March to the Scaffold was quite a bit more effective in its intended medium.

But I still didn't like it.

Skip ahead a month or two when, on a lazy day, I happened to ask my band director a few questions about how to read a full score. He responds by handing me a book and telling me to figure it out on my own. The book is, I see, entitled The Symphony, 1800-1880, and opening it, I find that it is nothing more than eight or nine symphonies, each by a different composer, in the full orchestral score. Every part, from the flutes down to the double basses and including all the percussion, is laid out side-by-side. Here, I see, are the composers' secrets: Beethoven's Eroica, Mendelssohn's Italian, Brahms's Third (which, sad to say, is the only one of Brahms's four symphonies that I've never liked), and…the Symphonie fantastique by Hector Berlioz.

I couldn't wait to get home. In went the tape, onto my lap went the book, and I started following along. I kept up well through the first movement's slow, dreamy opening, but I got lost a few times during the subsequent allegro. And then, about the third time I heard the main melody of that first movement, I realized that this was the melody that that single clarinet is quoting at the very end of the March to the Scaffold. And that same melody turns up in the second movement, a lilting waltz; and in the third movement, a ravishing pastoral slow movement; and in the last movement, which is titled "The Witches' Sabbath"!

It wasn't just the March to the Scaffold that was telling a story, I realized: the whole symphony is telling a story.

And as I taught myself how to read a score, by following along with the Symphonie fantastique, I became entranced and enchanted with the things this Berlioz does with the orchestra. Why use the flutes to double the melody in the violins? Well, it doesn't sound the same, does it? Makes it more "dreamy"….and when he restates the waltz theme in the second movement, he uses a harp for the waltz rhythm and the woodwinds for the melody…and an part for solo cornet…and that opening of the third movement! Depicting the shepherds of the hills with an English horn and an offstage oboe answering it! Depicting a thunderstorm in a slow movement!…and a demonic dance of the witches, complete with the Dies Irae and that weird sound by having the violins turn their bows over and slap the wooden bow against the strings!

Over time, I realized that it didn't really matter what the story of the Symphonie was; even then I had started being skeptical about music and its ability to "depict" anything concrete. What was more important is that I hated Berlioz, and then it was as if the Fates conspired to force me to re-evaluate him. And I did. Did I ever. I sought out other works by Berlioz, and then I read more about his life.

That was when I was hooked.

I have always thought that I would have been most comfortable in the Romantic era, and in the life of Berlioz I found proof. Here was a man of powerful appetites and desires: a man who fell in love with an actress when he saw her onstage in Hamlet, and he fell so completely that he ended up writing the Symphonie fantastique in her honor. (And could it be any surprise that, when he finally managed to marry her, it did not turn out well?) Here was a man who refused to adhere to the forms of his day: only one of his four Symphonies has the traditional four movements, and that one is heavily programatic with extensive use of a solo viola; he never wrote a concerto; he invented whole new groupings of instruments; for his Requiem he supplemented his full orchestra with four brass bands placed at the ordinal compass points in the Cathedral. Here was a man whose greatest literary loves were Shakespeare and Virgil, and here was a man whose music to this day has never been as appreciated within his homeland of France as outside it. Here was a man whose greatest work, Les Troyens, was never performed in his lifetime. Here was a man who viewed art in such stark terms that Schumann said of him: "Berlioz does not try to be pleasing and elegant. What he hates, he grasps fiercely by the hair; what he loves, he almost crushes in his fervor." That sounds familiar to me. I have myself been accused of going overboard in praise for things I admire, and going equally overboard in my attacks on things I dislike. But in this I have had good company, n'est ce pas?

How keenly I remember my disappointment when I watched the remarkable film Impressions de France at Disney World's Epcot, a thirty-minute travelogue of stunning French scenery scored with great French classical music – but not a single note of Berlioz! And how proud I was to have a scene in a Star Trek movie when Riker enters Picard's quarters and finds the Captain listening to blazing, fiery operatic music. "Bizet?" Riker asks. "Berlioz," answers Picard. In moments like these I realize that I take Berlioz personally. His music is my music, and if much of the world does not share that opinion, what of it? I, in admiring Berlioz, stand in the company of Wagner and Liszt. Pretty good company, that.

Ultimately, I think that every thoughtful person has that "tortured artist" whom they love dearly. For some it's Jim Morrison, or maybe John Lennon. Some respond to Sylvia Plath; others are moved by the sufferings of Van Gogh or Mozart. I think that if we're lucky enough to find someone who suffered for their art in much the same way that we see ourselves suffering (even if not nearly so dramatically), and we find them at the right time, the tumblers can somehow fall into place and something deep within our soul is unlocked. It's ours forever -- truly ours, in that sense that even when we find someone else who claims to love what we love, we're skeptical. Nobody loves Berlioz the way I love Berlioz.

And so be it.

1 comment:

If I had read this before - probably not, given my own blogging didn't start in 2005 - I don't recall it. Really interesting stuff!

Post a Comment